In the Orthodox Church, there is a figure revered not for his charisma or public speaking, not for his visionary leadership or institutional power, but for something far more intimate and haunting: his capacity to father souls.

He is the spiritual father: a priest, monk, or elder whose life is not his own, but whose prayerful presence becomes a guiding flame in the shadowed terrain of another’s inner world. While the modern West scrambles for life coaches, mentors, and productivity gurus, the Orthodox have preserved this deeply personal model of spiritual formation. For those in the Evangelical tradition seeking to reimagine discipleship and leadership, this ancient figure may hold surprising answers.

The Orthodox Model: A Relationship Beyond Roles

In Orthodox theology, the spiritual father is more than a pastor or a mentor. He is a spiritual physician. His vocation is not simply to teach but to heal. His knowledge is not theoretical, but experiential honed through ascetic struggle, inner silence, and decades of prayer. He does not instruct from afar. He walks beside his children, sometimes carrying them, sometimes confronting them, always loving them.

This role emerges most vividly in the monastic tradition. The starets, or elder, is not necessarily ordained, yet commands great authority because his life radiates the Spirit of God. He is sought out not for eloquence, but for holiness. According to Metropolitan Kallistos Ware, such a figure is recognized, not appointed. Like a prophet in Israel, the spiritual father in Orthodoxy is a man whom God has anointed and others, instinctively, come to him.

But while monasticism incubates this dynamic, the spiritual father is not confined to the cloister. Parish priests also serve in this role. And crucially, their authority does not arise from administrative status, but from the depth of their love, the trust they inspire, and their ability to guide others toward union with God.

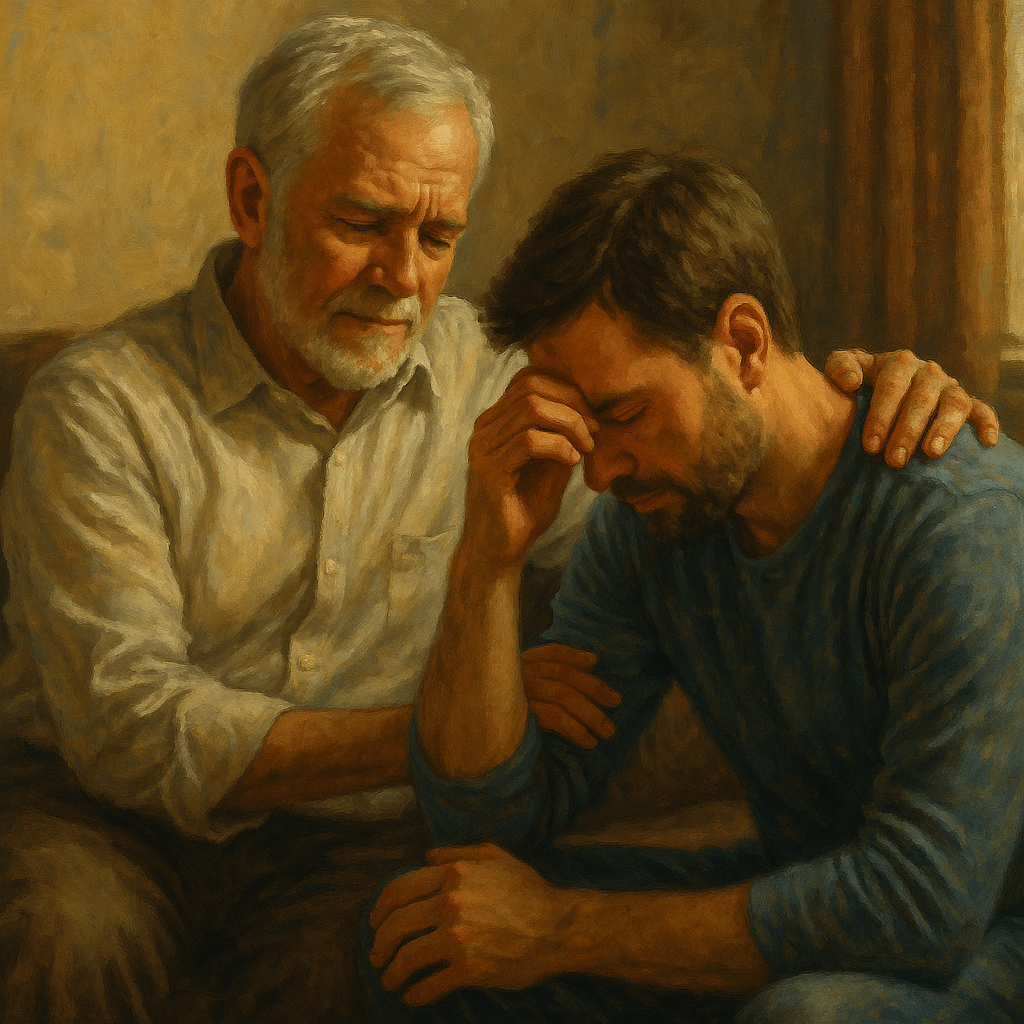

What results is not merely a “mentoring relationship,” but a familial bond. The child entrusts his soul to the father. The father, in turn, bears responsibility for that soul in prayer, counsel, rebuke, and sacramental accompaniment. This is not discipleship-as-course-material. It is life-on-life, spirit-with-spirit.

Mentorship and Its Modern Malaise

It is perhaps inevitable that American evangelicals would craft a more accessible model: the mentor. A mentor in this context is typically someone older, wiser, and willing to invest in a younger person’s growth. The model is sound, its biblical echoes evident in Paul’s relationship with Timothy or Naomi with Ruth.

Yet for all its merit, evangelical mentorship has too often been professionalized into a sanitized, segmented system ultimately severed from the raw intimacy of spiritual transformation. A mentor might meet you monthly. He might give excellent advice. But will he weep over your sins? Will he pray through the night for your children?

More often, the answer is no. Because the modern evangelical mentor, unlike the spiritual father, is not necessarily formed by asceticism. He is not vetted through years of suffering or prayer. He may be a good man but he is not necessarily a holy man. And that difference, subtle though it seems, changes everything.

Inside the Heart of the Spiritual Father

To understand the Orthodox vision, one must grasp the character of the spiritual father. He is, first and foremost, someone who has submitted himself to spiritual death. His ego has been broken. His desires reordered. His ears trained to the whispers of the Spirit.

He does not operate by program or principle, but by discernment. Each child is different. One may need silence. Another, rebuke. Another, freedom. The spiritual father becomes, in the words of Bishop Thomas Joseph, “a living icon of Christ:” a tangible presence through which the love and authority of the Lord are made manifest.

He is also deeply involved. In traditional Orthodox contexts, spiritual fathers are consulted on marriage, confession, vocations, and even financial decisions. Not because they seek control, but because their insight is trusted. Their job is not to manipulate, but to guide. When they speak, it is often with the weight of prophetic love.

This is not without danger. As the Orthodox themselves admit, spiritual fatherhood can be abused. It requires not only wisdom, but accountability and humility. Still, at its best, the relationship between spiritual father and child becomes a space of profound healing.

What Evangelicals Can Learn

For Evangelicals yearning to recapture the soul of discipleship, the Orthodox model offers not just a corrective, but a vision. But as a good evangelical, we must start by rooting this church tradition in Scripture.

Spiritual fatherhood is not a metaphorical flourish but a deeply embodied reality, threaded through both Testaments as a vital mode of relational formation. When Elijah passes his mantle to Elisha (2 Kings 2), the moment transcends institutional succession; it is a transmission of spirit and legacy, signaled by Elisha’s anguished cry, “My father! My father!” This dynamic finds its mature expression in the New Testament, where the Apostle Paul embraces not the role of teacher alone, but of father: “Though you have countless guides in Christ, you do not have many fathers. For I became your father in Christ Jesus through the gospel” (1 Cor. 4:15). His letters are saturated with paternal language: Timothy and Titus are not protégés, but “true sons” in the faith, and his ministry is shaped by the intimacy of spiritual parenthood. Jesus Himself, while warning against the misuse of honorific titles (Matt. 23:9), nevertheless frames discipleship in familial terms: “Whoever does the will of my Father in heaven is my brother and sister and mother” (Matt. 12:50), revealing that entry into the Kingdom is entry into a family. The Epistles echo this pattern as Paul describes his labor for the Galatians with maternal intensity, writing that he is “in the pains of childbirth until Christ is formed in you” (Gal. 4:19), demonstrating that spiritual fatherhood and motherhood are not about instruction alone, but about bearing and forming life in others through love, suffering, and abiding presence.

Scripture paints a vision of spiritual maturity as the product of deep relational investment. Paul’s model of discipleship calls the evangelical church to rediscover the essential role of spiritual parenting in its leadership and pastoral care. Rather than relegating discipleship to curriculum or mentorship to occasional coffee meetings, evangelical leaders could embrace the weightier calling of fathering and mothering believers into Christlikeness. This means cultivating long-term, intergenerational relationships rooted in love, humility, and prayer; it means pastors who not only preach, but pray and weep for their flock; it means lay leaders who raise spiritual children, not merely coach volunteers. In a culture increasingly marked by spiritual orphanhood, the church must become a household of faith in more than name.

Imagine a pastor who sees his congregation not as an audience to be entertained or a staff to be managed, but as sons and daughters to be raised. Imagine small groups not as affinity-based fellowships but as households of faith, with a seasoned spiritual mother or father at the helm. Imagine leadership development not as skills training but as spiritual apprenticeship.

The Crisis of the Fatherless Church

In both Eastern and Western Christianity, we face a crisis of spiritual orphanhood. Pastors burn out. Disciples drift. The young grow up with no one to guide them but TikTok therapists and YouTube preachers. The Church, in many places, has become efficient but not intimate.

Into this void steps the figure of the spiritual father. His presence says to the world: you are not alone. You do not have to heal yourself. You do not have to guess the way. I will walk with you. I will pray for you. I will fight for your soul.

And perhaps most importantly: I will love you not because I must, but because Christ first loved me.

Leave a comment